https://www.newscientist.com/article/2106382-head-transplant-teams-new-animal-tests-fail-to-convince-critics/

Head transplant team’s new animal tests fail to convince critics

Exclusive video shows a dog reportedly recovering the ability to walk after an injection into its damaged spinal cord, but the study has been criticised

X-ray of a broken neck

Head transplants could bring hope for those with broken necks

Science Photo Library

By Helen Thomson

Video footage seen by New Scientist appears to show a dog walking three weeks after its spinal cord was almost completely severed. Italian neurosurgeon Sergio Canavero says the technique used to treat the dog will make a human head transplant possible next year.

Canavero came to fame in 2015, when he claimed that the major hurdles to completing a head transplant are now surmountable. The idea is that someone paralysed from the neck down, for example, could have their head connected to the body of someone who is brain dead, restoring their ability to move (see box, below).

However, papers published today detailing the spinal cord repair technique applied to the dog have prompted other scientists to express concerns over the work. “These papers do not support moving forward in humans,” says Jerry Silver, a neuroscientist at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio.

.

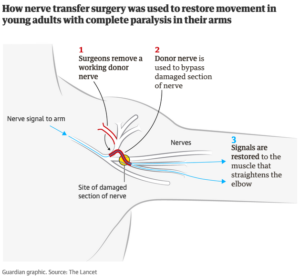

To fuse two ends of a spinal cord – either in someone who has broken their spine or to connect a transplanted head to a donor body – the ends of thousands of neurons need to meet across the join. Bunched together like strands of spaghetti, if these neurons don’t touch, they will grow past each other and never form the electricity-conducting pathways that send nerve impulses through the body.

Sergio Canavero

Sergio Canavero

Gughi Fassino/LUZphoto/Eyevine

In a series of three papers, all co-edited by Canavero for the journal Surgical Neurology International, researchers in South Korea and the US claim that a chemical called polyethylene glycol, or PEG, may help reconnect a severed spinal cord.

C-Yoon Kim at Konkuk University in Seoul and his team – who have been working closely with Canavero – severed the spinal cord of 16 mice. They then injected PEG into the gap between the cut ends of the spinal cord in half of the mice, while the rest were injected with saline. After four weeks, they report that five of the eight mice in the PEG group had regained some ability to move, compared with none of the control group. The other three PEG-treated mice died, as did all those in the control group.

Graphene scaffold

Meanwhile, a team at Rice University in Houston, Texas, has been working to develop a better version of PEG. Hearing about Canavero’s plans to use the solution in a human head transplant, the team believed it could improve it by adding graphene nanoribbons – an electrically conductive material that acts as a scaffold that neurons can grow along.

“My motivation is spinal cord repair. If this works, it’s going to have huge ramifications for spinal injuries,” says James Tour, who is part of the Rice team. “But we thought, if you’re going to be working towards a head transplant, you’re going to need this, so let us help you.”

“Read more: 6 things you’re dying to ask about head transplants”

PEG encourages the fat in cell membranes to mesh, bringing cells together – a process that may be enhanced by the nanoribbons, which are thought to provide scaffolding that encourages neurons to grow towards each other and connect. Tour says they do this in two ways: they are able to conduct electrical current, which helps neurons grow, and neurons seem to preferentially grow along this scaffolding, which helps them to meet and fuse together.

The South Korean team have nicknamed Tour’s enhanced solution Texas-PEG, and injected it into five rats’ spinal cords immediately after they had been severed. Five control rats were given saline instead.

Recovering movement

The following day, the team stimulated the rats’ spinal cords to see if any electrical activity could pass along it. According to the team’s paper, a small amount of electrical signals were present in the Texas-PEG group, but completely absent in the controls.

The group state that a flood in the lab subsequently killed four of the five rats that had been treated with Texas-PEG. Two days after surgery, the remaining rat is reported to have shown slight voluntary movement in all four paws, and a week later it was able to stand, but had difficulty balancing. After two weeks, the team says the rat could walk, stand up on his hind limbs and feed itself. “No recovery was observed in the controls,” says Kim.

In a final experiment, the South Korean team tested the original PEG in a dog immediately after it was given a near-complete cervical (neck) spinal lesion. Visual inspection suggested more than 90 per cent of its spinal cord had been severed – similar to what is seen in people who receive stab wounds to the spinal cord.

The following day, the dog was completely paralysed, but after three days, the team reports minimal movement in all four limbs. After two weeks, the dog was able to drag its hind limbs by its torso and forelimbs, and during the third week, it was able to walk. The team claims that the dog began to grab objects, wag its tail and resume a normal life. There was no control in the experiment.

Not ready for humans

New Scientist contacted more than 10 experts about these studies and the videos, but most were unwilling to comment publicly on the research.

Those who have commented say they have serious concerns about the reported results. “The dog is a case report, and you can’t learn very much from a single animal without controls,” says Silver. “They claim they cut the cervical cord 90 per cent but there’s no evidence of that in the paper, just some crude pictures.”

“Read more: First human head transplant could happen in two years”

Silver would prefer to see histology – microscopic tissue analysis – to confirm the dog’s spinal cord really was severely damaged before it recovered. As for the Texas-PEG paper, he says there is too little data. “You don’t report that four of your five treated animals drowned. You start again and increase your sample size,” says Silver.

Kim emphasises that his team’s experiments were proof of principle case studies, but says that “when combined, [they] confirm that a severed cord can be reconstructed”. The teams says its next paper will provide histological evidence confirming how damaged the animals’ spines were.

As for Canavero’s goal to conduct the first human head transplant soon, medical ethicist Arthur Caplan at New York University says the latest studies suggest this procedure is still some years away. “This work would put them about three or four years from repairing a spinal cord in humans,” he says. “It would put them maybe seven or eight from trying anything like a head transplant.”

How to transplant a head

Sergio Canavero first proposed attempting a human head transplant in 2013. He wants to use the surgery to extend the lives of people whose muscles and nerves have degenerated or whose organs are riddled with cancer. But there are many hurdles, such as fusing the spinal cord (see main story) and preventing the body’s immune system from rejecting the head.

The procedure will involve cooling both the head and the body it is to be moved to, to extend the time their cells can survive without oxygen. The tissue around the neck would then be dissected and the major blood vessels linked using tiny tubes, before the spinal cords of each person are cut.

The head would then be moved onto the donor body, and the ends of their spinal cords fused together using PEG. Next, the muscles and blood supply would be sutured. The recipient would be kept in a coma for three or four weeks to prevent movement. Implanted electrodes would be used to provide regular electrical stimulation to the spinal cord, because research suggests this can strengthen new nerve connections.

Canavero still thinks it could be possible to perform the first human head transplant by the end of 2017, depending upon finding a suitable donor. Several people have said they would like to volunteer to have their heads attached to a different body, while a hospital in Vietnam is reportedly keen to host the first surgery.